New naturalness

in planting design as a mirror of Nature.

BA. hons Garden Design.

Societe Scape.

e-mail: james@scapedesign.com

Abstract

How can a generative design model be applied to the historically complex

art of planting design?

In studying the chronology of planting design it is evident that

progress in this field has been slow and cyclical since ancient times. Man has

been importing foreign plants since history began, studying their horticultural

requirements and replanting them in their gardens. Gardens have been created

for the provision of food and pleasure, their layout - a representation of

their times.

However we have now reached the point where we have such a wealth of

cultural, historical and technological information at our disposal that it is virtually impossible for the

human brain to assimilate. Shouldn’t the

next step be to use artificial intelligence to take into account the natural

constraints of the site, the possible plant choices and the desires of the

client to produce a generative design using algorithms developed from these

parameters? As environmental concerns become more poignant the way we create

our surrounding landscapes is coming to the fore of our cultural and political

consciousness.

By studying the historical development of western planting design we can

see where the origin of today’s approach has come from;

A historical study of planting design.

Figure 1. The gardens of Mesopotamia 18th Century BC .

The gardens

of Mesopotamia are the earliest historical reference we have to the planting of

gardens. We know that their interest lay in attempting to recreate natural

planting effects, as in the celebrated hanging gardens of Babylon, however we

have no information how they applied this to an actual planting scheme.

Figure 2. The Egyptians 7th Cenury BC.

The

Egyptians used a formal planting pattern with everything in neat rows, the

plants were generally selected for their culinary or healing properties. There was however still a considerable

interest in the exotic and imported plants from far a field.

Figure 3. The Greeks 4th Century BC .

The Greeks shared the Mesopotamians love for nature. They felt the ‘Genus locus’ of a natural landscape was hallowed and sacred to be savoured in their natural state. Rather than trying to recreate this quality, they went to the source and built close to these spots. In the constant study of natural phenomena they marvelled at its complexity and chose to learn from it.

Figure 4. The Romans 2nd century BC.

The Romans like the Egyptians favoured a more orderly landscape and they carved great promenades, pergolas and arbours out of the natural landscape; planting them with cypress, rose and vine in an orderly fashion. They created a symbiotic connection between the villa and this organised landscape. Man was at ease with nature, whilst bringing order and discipline to its seeming chaos.

Figure 5. The Islamic garden 8th century

AD.

The Islamic garden applied symbolic meaning to four sided geometrical shapes, creating the fourfold garden ‘the Chaharbagh’. Plants were placed in an orderly fashion within the confines of the central square. Contrived planting was kept within the central square of the garden with more naturalistic plantings kept to the outer limits of the perimeter wall.

Figure 6. The Moors 11th century.

Plant variety had become more palatable by the time Moorish gardens really developed, water was used to create the main formal layout within the garden and more complex sequences of planting began to unfold in the surrounding garden beds. A strong emphasis was placed on flowers colour and scent. This is the first time that the sowing of mixed meadow seeds was recorded showing a delight in the ‘variety’ of nature.

Figure 7. The dark ages 15th century.

The dark ages saw a renewed fear of nature and the chaos in which it seems to exist. The gardens were walled, the planting design formal and structured. Plants men turned to writing books, huge developments were made in the nomenclature of plants and the study of their anatomy and horticultural requirements. The only way to plant nature was in an ordered and disciplined fashion to overcome the threat that it otherwise presented.

Figure 8. The Italian Renaissance 16th

century.

As man became more enlightened and educated

so his dominance over nature and her chaos gained confidence. The Italian renaissance gardens saw the reduction

of plant varieties used, formal gardens were laid out in a strict geometrical

fashion, trees pruned into rational forms, nature was harnessed into mans’

desired form. A good example of this type of garden is the Villa d’Este Pirro

Ligorio.

Figure 9. The French Renaissance 17th

century

.

The sheer wealth of the French renaissance gentry and royalty meant they were able to lay waste to vast woodlands, move mountains and dig great lakes. Nature was a thing of fable and myth, now man stood god-like and all nature made to bow to his manipulations. Plant variety was reductionalist, the form and structure that could be made from them was more important, the epitome being Le Notre’s Versailles.

Figure 10. The English Landscape Movement 18th

Century.

The English landscape movement used the landscape artists approach to designing gardens; remodeling hills, woodlands, lakes and rivers to create his compositions. But although appreciated for its beauty, nature’s variety was still not to be found here. Plants were used for their mass rather than for their natural effect. eg. Capability Brown’s Stowe House Buckinghamshire England.

Figure 11. The

Gardenesque style 19th Century .

With the dawning of the industrial revolution gardens were made accessible to a wider range of social classes and so we see the application of design on smaller gardens. To utilise these reduced spaces to greatest effect, plant selection became important. The change in scale meant that the plants were chosen individually for their flower, leaf and habit, and used in compositions, as in the landscape movement.

Humphrey Repton brought colour back to the gardens and developed the gardenesque style. But still nature was being categorised, analysed and formalised by man. Natures’ own chaos pared down into careful compositions and seasonal colour charts.

Figure 12. The English Promenade 19th

century.

In this same century we see the expansion of the British Empire, travel was widespread and more and more exotic species were readily available. This reflected directly on the planting design of the era as the material wealth grew so we see the arrival of throw away gardens with bedding plants being replaced season by season to maintain the maximum colour and effect, regardless of cost.

The Victorians were quite literally spoilt

for choice so we see everything everywhere scenario creating a mismatched

hybridization of planting design, in an attempt to create evermore impressive

and extravagant gardens as in those of Joseph Paxton at Crystal Palace.

Figure 13. The Wild Garden 19th century.

Understandably this excess invited contradiction, William Robinson advocated the return to the ‘Wild Garden’ that would develop naturally ‘ … this term is especially applied to the placing of exotic plants in places, and under conditions, where they will become established and take care of themselves… it does not necessarily mean the picturesque garden, for a garden maybe highly picturesque and yet in every part be the result of ceaseless care.’ [1] Finally nature returns to the garden in all its complexity.

Figure 14. A return to formalism 19th

century.

Sir Reginald Blomfield presented the contradiction championing formal gardens and declaring the landscape architect’s objective was not to ‘show thing as they are, but as they are not’. [2] Nature is separate to man and man makes gardens so why pretend it to be other.

Figure 15. Gertrude Jekyll-Edwin Lutyens 19th

century

The partnership of these two approaches - the formal and the wild was perhaps the logical next step. Gertrude Jekyll and Edwin Lutyens [3], created their own style, using a natural approach within a formal framework. Plants were chosen primarily for their colour and flowering time along with their form and habit. The regenerating pattern if undesired could always be dealt with by the gardener. Robinsons’ ideal is, therefore, still undermined by a desire for year round colour and harmonious colour combinations which were designed in accordance with Michel Chevreul’s colour wheel.

Figure 16. Piet Oudolf 20th century.

Todays great garden designers are taking the best of the old styles; Piet Oudolf [4], is following in Gertrude Jekylls footsteps and working with great swathes of colour, he has brought us a greater appreciation for the nature of a plant - its birth, life and death being used as an aesthetic, drawing us ever closer to nature. The regenerative nature of the plant is considered at a greater depth and the final result is much more self sustaining, the hand of the Gardener much less evident.

Figure 17. Gilles

Clement 20th Century.

Gilles Clement in his ‘Jardins de Mouvement’ allowed the plants natural regeneration to occur, selected plants are permitted to run across a more formal garden back ground as at ‘Parc Andre Citroen’. highlighting the plants natural tendencies in this way.

Figure 18. Hansen and Stahl 20th Century.

Hansen and Stahl [5], published a book on perennial planting where the reader is able to choose their plant by environmental factors, allowing them to understand the plants’ natural habits, generating a plant list which can be further broken down into its aesthetic requirements; ie, I want a purple spring flower that grows in rocks under trees, by using this sort of information new and interesting planting combinations can be created. Apply a set of algorithms to this plant database and a long list will emerge, giving us too much information, we need to hone this process as Carla Farsi [6], suggested in her paper on aesthetics and complexity when a pattern becomes too complex it is too confusing for us.

Figure 19. The New Naturalness 21st

Century.

The

algorithms in this case need to be sufficiently detailed to pare down this

complexity into a pattern which is pleasing to the eye, belying that which

created and is sustaining it. Perhaps specific patterns will emerge on the

computer screen just as the bluebells in woodland emerge where one of the

collections’ species dominates and naturally leads to a both a self sustaining and

aesthetically pleasing solution.

By linking an encyclopedic plant database with a graphic layout of the garden plan, a series of algorithms could be used to give the sufficient site information; soil, microenvironments, uses, etc. It could then graphically plot out a series of planting design solutions which the client could choose from. Each particular plot and client would produce an infinite set of fresh solutions.

Figure 20. Generative Planting Design Flow

Chart.

Environmental Factors. Plant characteristics. Client Desires.

+ +

- Climate - Size in maturity. - Style(Wild, formal, organic)

- Seasonal variation. - Speed of growth. - Irrigation or not.

+ +

- Daylight hours. - Habit. -

Colours.

- Soil type. - Flower colour. - Period of flowering.

- Gradient. - Period of flowering. - Uses.

- Graphic garden layout. - Leaf texture. - Speed of establishment.

- Water. - Regeneration pattern. - Species origin.

- Origin. - Maintenance

A plants natural generative tendencies are such that we need to ask at which point do we take the computer generated design and apply it, do we allow nature to continue the generative design or keep following the computers model?,

Should the resulting solution show what the planting will be like when it is fully matured or should it show the planting in its juvenile state?

Will the program need to back track to tell us how to plant the garden so that in 20 years it will reach its optimum aesthetic value?

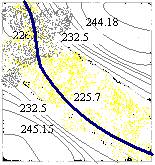

Figure 21. Timeline showing increasing natural complexity

with time.

Year 1. Year3. Year 6. Year 9. Year 12. Year 15.

Year 18.

.

This is not the static world of architecture where the materials may adjust with age as erosion slowly breaks them down. Gardens grow, plants compete for light and space. Soils are contaminated and eroded, infestations of pests or fungal attacks can destroy entire species, freak weather brings drought or floods, the wind and animals bring seed from other plants. It is certain the garden will not develop in the same way as the computer generated design.

Gardens generate, regenerate and create their own complex solutions. Throw a possible combination of plants well suited to naturalising in a certain environment and watch the process unfold. Should the gardener decide where to stop the progression so that chaos does not assume? Or through a generative approach to planting design can we come up with solutions which will find a natural equilibrium without the hand of ‘the gardener’ to keep things in order. Perhaps there is a case for the gardener to remove all weed species in the initial stages in order to allow the final establishment of the selected plants. But his role should be an ever diminishing task.

From the beginning of recorded history man has been working with plants to create gardens, either trying to harness nature or trying to replicate it, creating ever more complex planting solutions. The generative approach to creating a design solution has evolved from the study of complex organisms and systems in nature. By using the language of algorithms we can create an artificial system based on the in depth study of natural systems, new and creative highly complex solutions could evolve that work in harmony with the greatest generative artist – Nature.

References.

[1]. William

Robinson The English flower Garden, 1883

[2]. Sir Regianld Blomfield The Formal Garden in England 1892

[3]. Gertrude Jekyll Colour in the Flower Garden 1908

[4]. Henk Gerritsen & Piet Oudolf Dream Plants for the Natural Garden 1999

[5]. Hansen and Stahl Perennials and their garden habitats 1993

[6]. Carla Farsi Visual Synthesis and Esthetic Values 2004

Mitchell M. Waldrop Complexity: The Emerging Science at the Edge of

Order and Chaos

1993