“Natural Selection: a SteThoscopic Amphibious

Installation”

Mr T.J.Davis, BSc,

MA.

Sonic Arts Research

Centre, Queen’s University Belfast, UK

e-mail:

tdavis01@qub.ac.uk

Dr P.Rebelo, BMus,

MMus, PhD.

Sonic Arts Research

Centre, Queen’s University Belfast, UK

e-mail:

P.Rebelo@qub.ac.uk

Abstract

This paper discusses emergence as a

complex behaviour in the sound domain and presents a design strategy that was

used in the creation of the sound installation Natural Selection to encourage the perception of sonic emergence.

The interactions in Natural Selection

are based on an algorithm derived from an innately sonic emergent ecological

system found in nature, that of mating choices by female frogs within a calling

male frog chorus. This paper outlines the design and implementation of the

installation and describes the research behind its design, most notably the

notion of embodiment within a sonic environment and its importance to the

perception of sonic emergence.

1. Introduction

A fascination for models derived from natural organisms has

a long history of influence within the arts. In recent years, there have been

numerous implementations of algorithmic systems that model the phenomena of

emergent behaviour. In an attempt to reproduce the necessary conditions for

emergent behaviour to occur, these systems employ bottom-up strategies through

the definitions of simple rules for the behaviour of local agents.

In the context of sound design, a potential problem with

many of these systems is that the algorithms they are based on do not derive

from sound but typically from a system that exhibits perceived emergence

through the application of graphical (Boids) [13] or evolutionary (Genetic

Algorithm)[1] models. The implementation of these algorithms to a sound world is

then based on a more or less arbitrary mapping procedure between a graphical

and a sonic model.

The installation described here attempts to sidestep issues

pertaining to the mapping of graphical to sonic emergent systems by designing

the work through a carefully selected natively sonic emergent environment with

special consideration given to the notion that the phenomenon of emergence is

manifest in the dynamic listening system of a perceiver embodied within the

environment.

We have argued elsewhere [3] that the modeling of emergence

is linked to how we perceive it. In the context of emergent sound we feel it is

important to model behaviour that features intrinsic aspects of emergence in

the acoustic domain, in contrast to arbitrary mapping between domains.

'In

the same way that behaviours such as flocking are better understood from a

distance, we argue that sonic emergence can only be perceived when considering

the listener as an agent of that very behaviour. The ear does not act as a

stethoscope, listening in from the outside, but rather as a participant in a

space in which it takes the role of one, of many agents.' (Davis and Rebelo)

[3]

2. Ecological Model

This

installation is based on the listening ecology found in the model of female

frog mate selection within a calling male frog chorus. Through a study of

current research into the mating of frogs we have found that female frogs

select a mate from within the male frog chorus according to information

afforded to them through the temporal and spectral characteristics of their

calls [5]. Frogs have a complex auditory system that is designed to help them

recognise and respond to calls of their own species. They have a variety of

different calls for such situations as mating, distress, release, warning, rain

and definition of territory. The calls for different species are distinct in

temporal and spectral characteristics. This helps the frogs recognise calls of

their own species within a dense chorus [11].

The mating

calls of frog species under study can be characterised by four main parameters:

dominant call frequency (the frequency with the highest spectral intensity),

pulse rate, call rate and call duration. With dominant call frequency relating

to frog size, pulse rate relating to the ambient temperature of the

environment, for example the water temperature, and call rate and call duration

relating to the preference of each individual animal [8]. The characteristics

that were found to have the most effect on female choice of mate, were dominant

call frequency and call length [8]. It was found females preferred longer lower

calls, the pitch of the calls having a strong correlation to the body size of

the males and thus their

successfulness in mating. It has been found by Wollerman that a “female frog

could detect a single male’s calls mixed with the sounds of a chorus when the

intensity of the calls was equal to that of the chorus noise” [14]. Given that

there is a 6dB fall off in the intensity of the signal with each doubling of

distance away this means that for an average spaced chorus (0.08 males per

metre2 [14]), the female can only distinctly ‘hear’ between three

and five males at any one time

This

installation is based on a simple model of the interactions found between the

male frogs in the chorus with the user taking on the role of the female. Each

male frog is represented by a mechanical ‘sound object’, which consists of a

resonator excited by a motor. These sound objects have been designed to

represent the four main characteristics of the male frogs call: the size of the resonator being linked to

the dominant call frequency of the frog; the pulse rate is variable dependent

on lighting conditions (each “frog” is fitted with a light sensor the output of

which is affected by the user’s location causing disturbances to the light

source); the call duration is fixed but different for each frog.

2.1.

The Algorithm

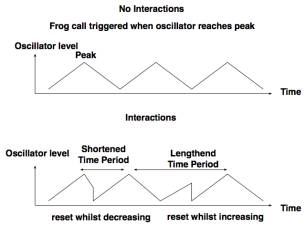

The rules that

govern the local interactions between the males are based on research that

suggests that female frogs prefer 'leading males', i.e. males that are

perceived by the female to be calling in front of the other frogs. [7]. To produce this effect the male frogs listen

to their nearest neighbours (the others being masked by the noise of the

chorus) and consciously alter their call rate so as not to coincide with other

males. To model this interaction each “frog” has a set call rate which is

modified through the application of an algorithm based on a resettable

oscillator. Each of the frogs is wired to its two nearest neighbours to

resemble the listening conditions in the wild [11]. If a “frog” 'hears' a

neighbour making its call, by virtue of receiving a current down a wire it

resets its oscillator to 1 thus inhibiting its own call and lengthening or

shortening its own call rate. The local interaction between the male frogs is

the algorithmic structure that has been set up to exhibit emergent results. The

temporal form of the piece is not only governed by the frogs own set call rate

but by the interactions of the frogs with their nearest neighbours.

'Form is a dynamic

process taking place at the micro, meso and macro levels. When properties not

explicitly determined by specific parameters emerge at different levels, we

witness a pattern-formation process. In this case form is not defined by the algorithmic

parameters of the piece but results from the interaction among its sonic

elements. in a general sense higher level forms or behaviors resulting from

interaction of two or more systems' [9]

Fig 1 Resetable Oscillator Model

2.2 Design Considerations

This

installation attempts to promote a ‘learning through interested interaction

approach’. [12], thus there are no instructions or rules set out for the user

to follow and there are no prescribed levels or modes of interaction. If this

approach is to work it is important that the installation compels the user to

interact through generating interest in the sound objects, it is also important

that the user feels free to approach these sound objects and that the spatial

setup of the installation allows for a liberated mode of enquiry. Since there

is no statement of artistic intention for the piece the mode of communication

between the sound objects has to become apparent through interaction and

investigation. To make this

communication explicit a network of wires suspended between the objects

suggests links and interactions within the installation space. This suspension is

well-over head height and suggesting an enclosed but accessible space,

hopefully encouraging visitors to “enter” the space inhabited by the sound

objects.

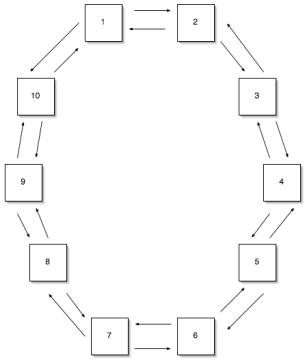

The sound

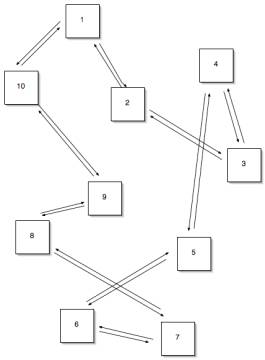

objects were first laid out in a circular form, [Fig 2], so as connections to

their two nearest neighbours is easily obtained. The order of the sound objects

is then shuffled [Fig 3] to generate a more non-linear spatial structure, so

that it is now possible to stand within the proximity of a small cluster of

sound objects, or to move to a more open space dominated by fewer objects. We

will argue later that this facility for the user to define their level of

engagement and embodiment within the piece is important in leading the ear in

the perception of emergence.