New Naturality

of Artificial World: a Thread Spider Web

S.L.M.C. Titotto, Arq.

School of

Architecture and Town Planning, University of Sao Paulo, Sao Paulo, Brazil.

e-mail:

titotto@hotmail.com

Abstract

This work outlines results of an

ongoing investigation on aesthetics, using spider webs as physical support and

point of departure for spatial reflections.

One of the practical results is a

piece of installation art to be performed at the 7th Generative Art

Conference GA2004, which transits on the borderline between fine arts,

architecture, as well as taking into consideration some structural engineering

concepts.

In this context, a few artistic

installations have already been performed in museums and galleries in Sao

Paulo, in order to explore the intrinsic relationships between the technology

of the cable structural systems and the aesthetic possibilities open by their

characteristic forms, interacting with light, color, textures, movement and

environment.

1. Motivation

Forms found in nature are shaped for

maximum efficiency, transferring the required amount of force with the least

amount of material. In “On Growth and Form”, D’Arcy Thompson suggests the

shapes of living things are largely the result of adaptation to physical forces

[1].

All natural structures must resist

the physical forces of tension and compression. To adapt and increase

efficiency, natural forms prefer tension members because compression members

have a propensity to buckle. It uses the maximum amount of tension members

concentrates compression into localized regions.

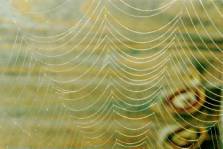

Figures 1, 2. Dew drops

on a spider web: jewellery semblance

The

web is made of a network of tension strands, with the spider and captured prey

acting as localized compression struts. Since the web must resist the same

physical forces as civil structures, the web’s form provides an elegant model

by which maximizes efficiency.

Efficient

forms are often aesthetically pleasing. Some of the terms we commonly use to

describe works of art, such as balance and symmetry, are derived from

functional considerations, such as efficiency [2].

Figure 3. Web Sampler #50, Pae White, 2001. Gallery, 1301PE.

Works on Paper. Materials: Spider web on magenta coated stock.

However,

an efficient design is not necessarily an aesthetically pleasing one. Numerous

structures exist that are efficient but lack aesthetic value. Connecting design

to natural forms can avoid this pitfall. An important component in our

aesthetic appreciation of nature is our desire to feel an emotional connection

with our environment.

Aldersey-Williams

[3] points out that in Jungian psychology, a wild animal often represents the

Self, and we immerse ourselves in nature to nourish this connection. When

organic forms inspire us, we can design efficient structures that mirror them –

works of structural

art that arouse our sense of harmony with our environment.

The structurally efficient form evokes aesthetic pleasure because it echoes our emotional connections with biological forms.

2. Installation art

4

4

5

5

Figure 4.Nature Spider web; 5.Nature-inspired web

made of rubber threads, Silvia Titotto, 2004.

Figure 6. In Exhibition:

Web (rubber, thread, rocks), Silvia Titotto and Jung Chi, 2004.

2.1 GA2004 Installation art: some principles

The visitors who aim to go through the artwork

passages made of flexible threads might have the possibility of feeling of

being integrated to the oeuvre, while they are exploring it.

The material translucency aggregates subtleness values to the web, which

is more or less intense all along the porches, depending on the wire quantity.

The

structural threads running from the outside of the web to the centre provide

great firmness, while the catching threads running around the structural

threads ensure the necessary flexibility.

Figure 7. Structural principles of the nature

spider web

2.2 Execution

2.2.1 Material for web

Lycra 120 Dernier,

DuPont technology

Cristals

2.2.2 Dimensions

According to room sizes (possibly 3m x 3m x 3m)

2.2.3 Light

Light spots (100W each) for the

tonal intensity.

2.2.4 Foundation

Hanging hooks from the ceiling, walls and floor.

3. Acknowledgments

Thanks to

FAPESP for supporting this research.

4. References

[1] Willis, Delta. The Sand Dollar and the Slide

Rule: Drawing Blueprints from Nature. New York: Addison-Wesley Publishing

Company, 1995.

[2] French, Michael. Invention and Evolution: Design

in Nature and Engineering. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1994.

[3]Aldersey-Williams, Hugh. Zoomorphic: New Animal Architecture. New York: Harper Design International, 2003.